Everything You Need to Know About COVID-19 Testing

The road to “normalcy” and the gradual reopening of the U.S. economy depends on reliable and widely available SARS-CoV-2 testing.

While a vaccine and treatment for the coronavirus are part of the larger mission, there is global consensus among scientists, governments and private industry experts that strong, pervasive and accurate coronavirus testing is the key to getting to the other side of the coronavirus pandemic.

There is far less clarity around what tests are available, who is eligible to receive one, which tests are most accurate and effective, and what different types of tests are being conducted. There are also discrepancies in the data collection around what conducting a “test” actually means. Is a “test” complete when a sample is collected from a patient? Is it incomplete if the sample can’t be sent to the lab because of a lack of shipping supplies? Is a test “complete” only after the lab processes it or is it when a patient gets a result?

Ambiguities and questions about coronavirus testing abound, so let’s take a closer look at the facts about coronavirus testing in the U.S.

What are the Different Types of Coronavirus Tests?

There are two primary test types available: molecular and serological.

Molecular testing:

Molecular testing was the first coronavirus testing type approved for use in the U.S. Since Roche became the first company with approved molecular testing on March 16, 2020, dozens of companies now have a molecular test on the market, most of which have been approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

The vast majority of these EUA test approvals are for polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, molecular tests. PCR tests, generally speaking, are a method of analyzing a short sequence of DNA or RNA in a sample containing only minute quantities of DNA. Put simply, a PCR test can take small samples of DNA and amplify them so that they can be analyzed.

PCR tests can only detect antigens, not antibodies, meaning they are only effective for identifying individuals actively infected with SARS-CoV-2. Since SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus, an additional step is required; a reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme is added to create a DNA template before the PCR takes place. Thus, PCR tests, which have been around since 1985, are called RT-PCR tests when used to test for SARS-CoV-2.

Samples for RT-PCR tests are collected, in most cases, via swabbing the nose or throat. These samples are then sent to a certified laboratory for analysis via the RT-PCR testing process.

At the outset of the coronavirus pandemic, RT-PCR testing, in some cases, had a much higher false-positive rate — some believe this rate to have been as high as 30% — and was labor-intensive, with several manual, hands-on steps being required that led to a higher possibility of human error. Over time, RT-PCR testing accuracy seems to be improving significantly due to better processing automation. The speed of results is improving as well, with some tests generating results within minutes where early on it could take several days to complete.

Companies have done a remarkable job improving coronavirus testing in a very short period of time, going from a longer, more complex process to now having real-time, point-of-care testing available that can generate results rapidly, in some cases while a healthcare professional is still with a patient. In late March, the FDA granted EUA to Abbott for its PCR coronavirus test that could generate positive results in as little as 5 minutes and negative results in just 13 minutes. Labcorp’s Pixel recently received EUA, becoming the first in-home coronavirus test kit of its kind.

While testing effectiveness and results are being generated much more quickly, challenges remain in the area of material availability and overall testing capacity in the U.S. According to the CDC, 97 labs are verified to offer testing and as of May 4th and over 7,000,000 tests have been completed in the U.S., according to Johns Hopkins. Test completion numbers are rising and the availability of tests is improving, but they are not yet where they need to be.

Serology testing:

Serology tests have only more recently received EUA from the FDA. Serology tests are used to identify antibodies generated by an individual’s immune system to fight SARS-CoV-2. The key difference between RT-PCR and serology tests is that the former can only detect active infections whereas the latter can tell us how much of the U.S. population has been infected overall.

Antibodies are only detectable, in most cases, a week or two post-infection and therefore many individuals might have already recovered from COVID-19. Having accurate antibody testing is critical to identifying who has been infected and what portion of the population might have already developed immunity to the coronavirus. This kind of testing will allow the U.S. to determine when the population is approaching “herd immunity” levels that could stop the coronavirus’ circulation.

Serology testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is conducted via blood samples. Serum, which is a component of blood, is then analyzed for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by introducing the “spike protein” to a blood sample. The “spike protein” is the mechanism by which the virus invades cells. If a patient has come in contact with the coronavirus, antibodies will be present and the test will detect them.

According to MIT, a good way of thinking about the differences between RT-PCR tests and serology tests is that the serology test is seeking the answer to a different question — not “Does this person have coronavirus?” but rather “Has this person’s body ever seen the germ at all?”

Currently, there are a host of serological tests available. The FDA allowed a flood of serology tests into the market without EUA and many of these tests have proven to have high false-positive rates, which has been problematic to U.S. testing efforts. On May 4th, the FDA revised its guidance and is now requiring all companies offering serology testing to apply for EUA status.

Until just recently, the FDA had issued only one EUA for a serological test in early April 2020, to Cellex, Inc. There are now 11 serology tests granted EUAs, including new tests from Roche and Euroimmun US Inc. that were granted EUA in early May. These tests with EUA have much higher specificity levels, some nearing 100%, meaning there is a very low false-positive rate.

What Materials are Required for Coronavirus Testing?

In order to understand the test, and what “completion” actually means, one also has to know what materials are required to take a test from collection to results. It’s important to understand that a patient getting swabbed or a blood sample getting collected is only the first stage of the testing process.

It has been widely reported that shortages of key testing materials have hindered more widespread coronavirus testing. A variety of materials are needed in vast quantities to support testing from the collection point, through sample shipping and finally to processing and results delivery.

Swabs and personal protective equipment (PPE)

Swabs are required for RT-PCR tests to facilitate the collection of samples from the throat or nose. In addition, PPE like face shields and protective gowns are needed to keep frontline workers safe from infection. These swabs and PPE have been in short supply with manufacturers struggling to keep up with demand. If a sample cannot be collected, and if healthcare workers get infected due to lack of PPE, testing capacity cannot be ramped up to the levels needed.

What is Involved with Shipping Test Samples?

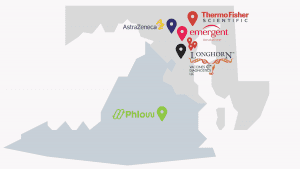

Once a sample is collected, it needs to be safely transported to the lab in order to preserve the quality and integrity of the sample. This requires a steady supply of transport media and the specialized tubes used to contain the sample for shipping. In addition, these samples must be cold-shipped or frozen in route and inactivated in a special Biological Containment Device, to maintain the sample’s stability and to protect those doing the lab testing. It has been well-documented that a shortage of transport media and tubes were bottlenecks in the testing ramp-up process in the early days of the pandemic response. Longhorn Vaccines & Diagnostics, a company located in the BioHealth Capital Region, along with other diagnostic suppliers across the U.S., have been helping to remedy these ongoing albeit improving issues.

Why are Reagents Important to COVID-19 Testing?

Reagents are the materials that make testing samples possible. Both RT-PCR and serology tests require pure reagents to facilitate the reactions needed to produce an accurate result. Enzymes, probes and primers are a few of the reagents required for testing. For example, in order for RT-PCR testing to work, two primers, or short pieces of single-stranded DNA, are used to bind to sections of template DNA to indicate the section of the DNA to be copied. This is critical to amplifying the material in great enough numbers to be analyzed.

Without an abundant supply or primers and other key reagents, the testing simply cannot be completed.

The coronavirus testing situation continues to evolve on an almost daily basis and will likely continue to do so as researchers, companies and government agencies strive to improve the country’s testing capacity and efficacy.

Most recently, a test developed by the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), located in Arlington, Virginia is said to have the potential to identify SARS-CoV-2 carriers before they become infectious.

What’s next on the COVID-19 testing horizon? No one is certain. The only certainty is that better, more accurate and more widespread RT-PCR and antibody testing are the keys to returning the U.S. to some sense of normalcy.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Steve brings nearly twenty years of experience in marketing and content creation to the WorkForce Genetics team. He loves writing engaging content and working with partners, companies, and individuals to share their unique stories and showcase their work. Steve holds a BA in English from Providence College and an MA in American Literature from Montclair State University. He lives in Frederick, Maryland with his wife, two sons, and the family dog.